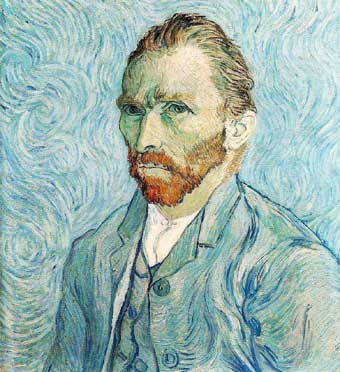

This week I met a Christian, who has never experience kindness from the church or Christians around her. She was marveled by our generosity and kindness. There is something very wrong in the contemporary evangelical Christianity. This resonates in the story of Van Gogh. The famous painter Vincent Van Gogh, sought to be a clergymen. He loved to read the bible, teach in Sunday school (when he was living in London), and listen to various sermons—his letters to brother and sister are filled with bible quotations. His failure to gain admissions to Amsterdam University for the theological training as clergy men, resulted in going to an evangelical college. He graduated and commissioned to the Belgian mission field, where he became cynical of the evangelical faith. In his later years, he distant himself from the religion—failure to find employment, or sell his paintings and mental disorders drove him to take his own life, in a corn field, where he was drawing. This is an excerpt taken from the lovely book called Evangelical Disenchantment by Dr. David Hempton:

No doubt piqued by a sense of rejection, and schooled in the evils of hypocrisy by his readings in Shakespeare, Dickens, and Harrier Beecher Stowe, Vincent developed a passionate cynicism for those in authority, especially those in religious authority in the same way that he lost respect for commercial art dealers in Paris and London, and self-serving theological educators in Amsterdam, he grew disenchanted with the evangelical leaders hip he encountered in Belgium. "I must tell you," he wrote Theo, "that with evangelists it is the same as with artists. There is an old academic school, often detestable, tyrannical, the accumulation of horrors, men who wear a cuirass, a steel armor, of prejudices and conventions; when these people arc in charge of alEiirs, they dispose of positions, and by a system of red tape they try to keep their protégés in their places and to exclude the other man." Comparing the spirituality of evangelical worthies to that of shakespeare's drunken Falstatf (very Dickensian), van Gogh concluded that they were incapable of normal human emotions or of anything approaching clear-sightedness. A similar distrust of religious professionals shows up a year later, when, after yet another bout of unrequited love, this time with his cousin Kee Vos,he wrote that the object of his love was in a mental prison imposed by the "Jesuitism of clergymen," which no longer had a hold on him because he knew some of "the dessojis de canes": "For me that God of the clergymen is as dead as a doornail. But am I an atheist for all that? The clergymen considering so—so be it—but I love, and how could I feel love if I did not live and others did not live. Now call it God, or human nature or whatever you like, but there is something which I cannot define in a system though it is very much alive and very real, and see that as God, or just as good as God." Van Gogh's criticism of the religious professionals he had once sought to emulate was accompanied by a more inclusive and less mutually competitive view of religion, art, literature, and spirituality than was the case in his evangelical phase. "I think that everything which is really good and beautiful—of inner moral, spiritual and sublime beauty in men and their works—comes from God, and all which is bad and wrong in men and their works is not of God, and God does not approve of it." In this way van Gogh was able to move beyond what was at times an antithetical view of religion and art to one that sought unity in all "the many things one must believe and love." Thus he could find something of Rembrandt in Shakespeare and something of the Gospel in Rembrandt and so on. Nevertheless, resolutions of old warring members did not come easily to van Gogh, and not all was resolved. He recognized that he had spent five years of his life "more or less without employment, wandering here and there," and that he was still without a suitable vocation, financial resources, familial respect, or his own family. He described himself as a caged bird imprisoned by adverse circumstances, a damaged reputation, and insufficient redeeming love. Even if his cage had not sprung open, something substantial changed in him in the years 1879—80. After parting company with the Belgian evangelicals, never again are his letters dominated by endless scriptural quotations, pious instructions, and a desire to find some form of sacrificial Christian service. Van Gogh, the evangelical Protestant, was buried somewhere in the coal mines of the Borinage. The person who emerged from the Belgian "black country" was just as much a tortured soul as the person who entered it,

but never again was the torture prescribed for him by some form of intense biblical Christianity. Van Gogh came to believe that love was the more excellent way and that art, for better or worse, was his passion. In 1880 he wrote, "the best way to know God is to love many things. Love a friend, a wife, something—whatever you like—and you will soon be on the way to know more about Him."

Source: David Hempton, Evangelical Disenchantment: Nine Portraits of Faith and Doubt. (New Haven:Yale University Press, 2008), 128-29.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment